photography

MARY ROZZI

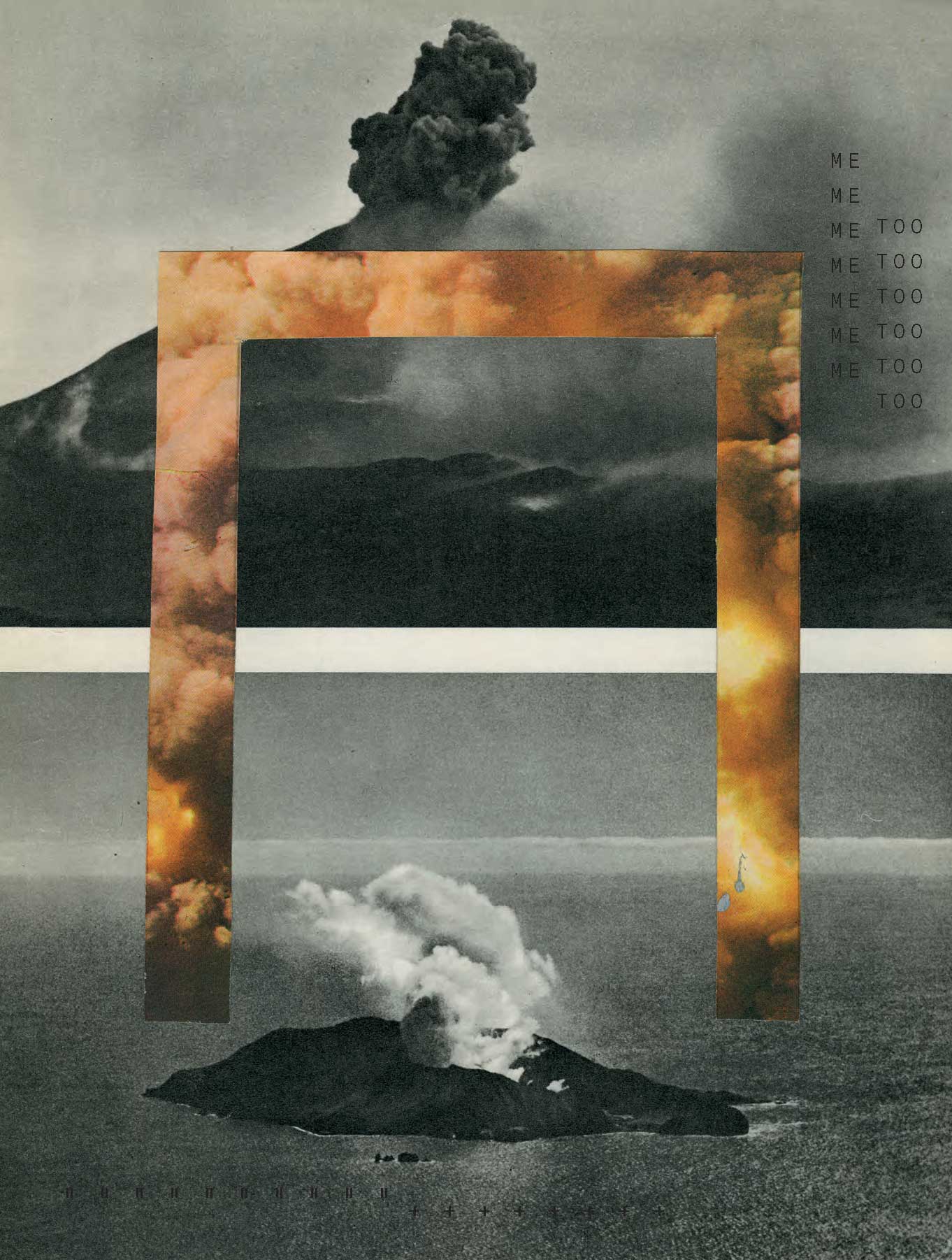

From Me Too to #MeToo

I. BEHIND CLOSED DOORS

Me too: it’s a simple phrase, and its simplicity helped it go viral, seemingly overnight. As it began to spread around the world, white feminists scrambled to give credit to the woman who first coined the phrase over a decade ago—anti-sexual violence activist Tarana Burke. What seems to have been missed between the Golden Globes red carpet and New Years Eve ball drop, is that Burke wasn’t thinking about workplace sexual harassment when she started the movement. She was thinking about the kind of sexual violence and abuse that happens to women—often very young women, often girls, and often girls of color—behind closed doors.

It’s not that the two are unrelated. Sexual harassment in the workplace “falls on the spectrum of sexual violence,” Burke says during our recent phone conversation, “and our work is about interrupting sexual violence.” Think about who has the capability to speak out about sexual harassment: it’s women who work outside the home, often in fancy, white-collar jobs. Think about the industries that have reckoned with sexual harassment: Hollywood, journalism, politics. They’re industries that face outward, they have a public. The problem, according to Burke, is when “people couch the whole movement under the idea of sexual harassment in the workplace. It narrows the scope, it eliminates the scores and scores of people who are speaking out about a broader idea of sexual violence.” Tarana has spent her career in the trenches with those scores of people who are speaking out, and is using her time in the spotlight to bring attention and resources to the fight.

Burke has spent decades working with middle and high school-aged girls. “We don’t talk about sexual harassment even in schools,” she says. Child sexual abuse is still relegated to the shadowy corners of public discourse. So is intimate partner violence. So is rape, and incest. The challenge of “me too” going from a grassroots movement to a hashtag is that those stories might be lost. However, women like Burke are working to finally shine a spotlight into those shadowy corners.

“People don’t want to acknowledge that it’s going on in their families or that it’s happening in their communities. It’s like a self fulfilling prophecy: you don’t talk about it, and it happens; you don’t talk about it, and it happens some more. We go around and around in circles.”

II. BREAK THE TABOO

Though broadening Me Too to #MeToo has posed problems, it has also had the immeasurably valuable effect of moving conversations about sexual violence from the shadows into the mainstream. In 2017, Time magazine named “The Silence Breakers” of the movement their person of the year, and Burke was among those honored. At its most basic level, #MeToo has sliced through the heavy curtain of silence around sexual violence, and the stories have flooded out.

“Sexual violence is still largely taboo,” says Burke. “People don’t wanna talk about it. It’s a very, very uncomfortable subject. A lot of people don’t want to believe it. A lot of people don’t want to believe that it’s real and that it happens.” It creates a vicious cycle. “All of that plays into us shying away from it as a topic. People don’t want to acknowledge that it’s going on in their families or that it’s happening in their communities. It’s like a self fulfilling prophecy: you don’t talk about it, and it happens; you don’t talk about it, and it happens some more. We go around and around in circles.”

During my conversation with Burke, as she explained the cycle of silence around sexual violence, I thought of a night last fall. The Harvey Weinstein story had just come out, and #MeToo flooded my Twitter and Instagram feeds. I was out with a group of women who I work with. We drank wine, and the stories come out fast and hard. We started off talking about the news, but then, seamlessly, we began to talk about ourselves. We had all been sexually assaulted, and now it was starting to feel like we could call it forth from the secret, shameful places in our hearts.

“Having something like Me Too makes it so easy for people,” Tarana says, “It gives them entry into this world where they can talk about sexual violence in a very uninhibited, free way. And I think that’s the beauty of it.”

Nearly 18 million women have reported a sexual assault in the United States since 1998. That’s almost 900,000 a year, or about 2,500 a day. And those are only sexual assaults that have been reported. RAINN, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, estimates that only a third of sexual assaults are reported, so these numbers only represent a fraction of the women who experience sexual violence. It is ubiquitous. “One of the things I’m fascinated by,” Tarana explains, “is that sexual violence is so pervasive and it permeates every part of our lives and every part of our world. And yet, people who are survivors of sexual violence feel so isolated. The overwhelming thing that you hear from survivors is that they feel alone in their circumstances.” That’s why “Me Too” is much more than an empty slogan. Being able to say, “it’s happening to me too,” is transformative. It makes the survivor feel less alone.

When asked if it’s difficult to guide people towards healing from sexual violence, Tarana says no. It’s not hard work, but it is a lot of heart work. You have to be present, you have to be open. “You gotta put a lot of heart into it and you gotta operate from your heart all the time—and that can be difficult.”

III. AN ORDINARY EXTRAORDINARY STORY

Tarana has spent her career working with young people. In the mid-2000s, she and her organization, Just Be Inc., did a twelve-week intensive leadership training program with high school girls of color. The purpose, she says, was not to build self esteem—that empty phrase that gets shoved down our throats from childhood—but to build self worth. The difference, Tarana explains, is that self esteem depends on living up to outside expectations. Self worth is about building up an internal foundation of worthiness. “We pump young people, young girls especially, full of platitudes all the time,” she sighs. “And then they go out into a world that tells them something different. That constantly tries to undervalue them, that constantly tries to undermine their worth.” The work Just Be did was to root black and brown girls in a sense of worthiness by teaching them their history and culture.

In the workshops, Tarana and her colleagues would teach the girls the backstories of celebrities whose names they knew, but whose challenges they did not: Gabrielle Union, Oprah Winfrey, Mary J. Blige, Queen Latifah, Missy Elliott. They would use these famous women’s stories to show how a life can start one way—with trauma, say, or abuse—but that the trajectory of their life is not determined by those early experiences. One can imagine that someday, some workshop facilitator of the future, might put Tarana on that list.

“For me, it was really difficult to do the work and to deal with the amount of sexual violence that the young people who we were working with were facing,” Tarana says. “They were constantly coming to us and talking to us about it. If you haven’t healed from the things that have caused you trauma, it is going to be hard to understand your self worth.”

In the 2005-2006 school year, while Tarana and her colleagues were doing the Just Be program with students, that they first developed a workshop called Me Too. The workshop was about giving young people language, and understanding the terms around sexual violence: the definition of rape, statutory rape, molestation, incest, and sexual harassment. Understanding the language, they reasoned, would help the girls understand their experiences and name them, and it would bring them out of isolation and toward healing.

Tarana continues to travel around the country doing these workshops. “I actually literally just did this workshop in Montgomery last Saturday,” she says. “As I’m traveling around, most cities I go to, I try to do a community workshop as well as a speech.”

Tarana is now working on a memoir called Here the Light Enters: The Founding of the ‘Me Too’ Movement, coming out early next year. In it, she will use her own story as a window into the experience of sexual violence in communities of color, and especially the absence of resources in those communities. In telling her story—her “ordinary extraordinary story”—she will tell the bigger story of the kind of trauma that so many black girls around the country experience that we don’t acknowledge.

“If you haven’t healed from the things that have caused you trauma, it is going to be hard to understand your self worth.”

IV. BUILD POWER

“I think of survivors as a power base,” says Tarana. They are a constituency, a community of people with common interests. As she looks toward the future, she is trying to harness that power and use it to change the culture. “After years of working with both survivors of sexual violence and young people, I’ve learned that trauma manifests in our lives in communities of color in very different ways. A lot of times it can be acts of violence,” she says. “It can come out in all these other ways that get couched under the idea that ‘These are just challenging children. They’re just unruly and undisciplined.’ As opposed to acknowledging that they come from a background of trauma.”

The next phase of the Me Too movement is to change the narrative. Tarana often talks about how survivors should be placed at the forefront of solutions for ending sexual violence. But what does that actually mean? “All of these conversations about sexual harassment in the workplace and all these conversations about perpetrators is not helpful to survivors. It’s not helpful to people who are out there asking for help and looking for resources.” The debate about what it’s doing to hiscareer or the conversation about his faults and ethics is not the point. The point is the survivor, and her healing.

When asked who is doing really good, bootson-the-ground work, Tarana gushes. She can instantly think of a dozen people and organizations: her fellow members of Just Beginnings Collaborative, a group of organizers who are working to end child sexual abuse, “Aishah Shahidah Simmons is in it, and she did NO! The Rape Documentary. She’s a long time anti-sexual violence advocate, she works against sexual violence. More than two decades of work. Amita Swadhin who works with the trans and gender nonconforming community. Ignacio Rivera is also in it. He is also a trans activist.” Tarana and her colleagues don’t want to waste this moment, and that may mean turning the ship in a different direction. It means bringing the focus back to these people, who aren’t famous, at every turn.

V. A MOVEMENT, NOT A MOMENT

Me Too started as a social movement. That means long-term, dedicated, and organized. It went viral in a moment, but it will be sustained by those who built it up brick by brick. “Because the moment happened so quickly, we are in a place where we have to scale up a lot of the work that we were doing,” Tarana says. “We have a way, way, way bigger audience than we’ve had in the past. And so, the first thing we’re doing is we’re building a virtual community. There’s not a place that exists right now online that survivors can come to to find solace. I think of it as sort of a la carte. Craft your own journey. I don’t wanna ever tell somebody this is how you heal. But I want to make as many resources available so that people can cherry pick what they need.” The website is called metoomvmt.org and and is currently in the process of development. It will be membership based, but you won’t have to be a member to use resources. Me Too is also expanding its offline organizing. They will be offering training and certification for survivors and allies and advocates. The only way to truly scale up the grassroots work of Me Too is train more organizers and policy makers to do on-the-ground work in their own towns and cities. Tarana is a remarkable advocate, organizer, and facilitator, but she can’t be the pillar of every community. Nor does she want to be. The goal of Me Too is to have survivors and allies in their communities interrupting sexual violence at the roots. “I’m out here looking for resources so we can build this thing that never existed. I know we are capable,” Tarana insists. “I know it is possible. When we have the resources, we’ll be able to do it.”