photography

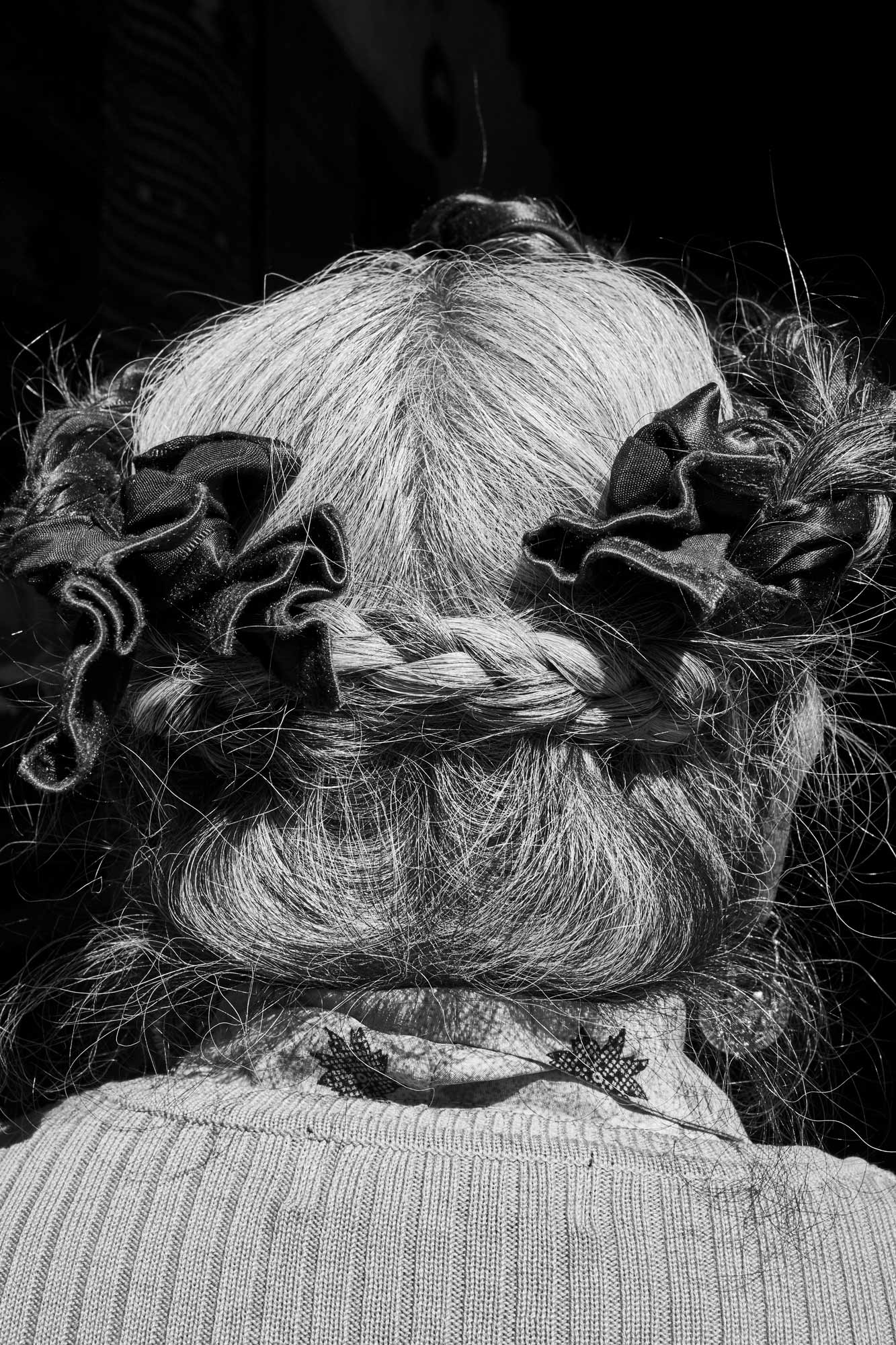

ANDREA GENTL

Las Mujeres Fuertes

ANDREA GENTL TRAVELED TO OAXACA, MEXICO TO PHOTOGRAPH THE WOMEN WHO ARE KEEPING LOCAL TRADITIONS ALIVE, AND PAVING THE WAY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS OF ARTISANS AND BUSINESSWOMEN.

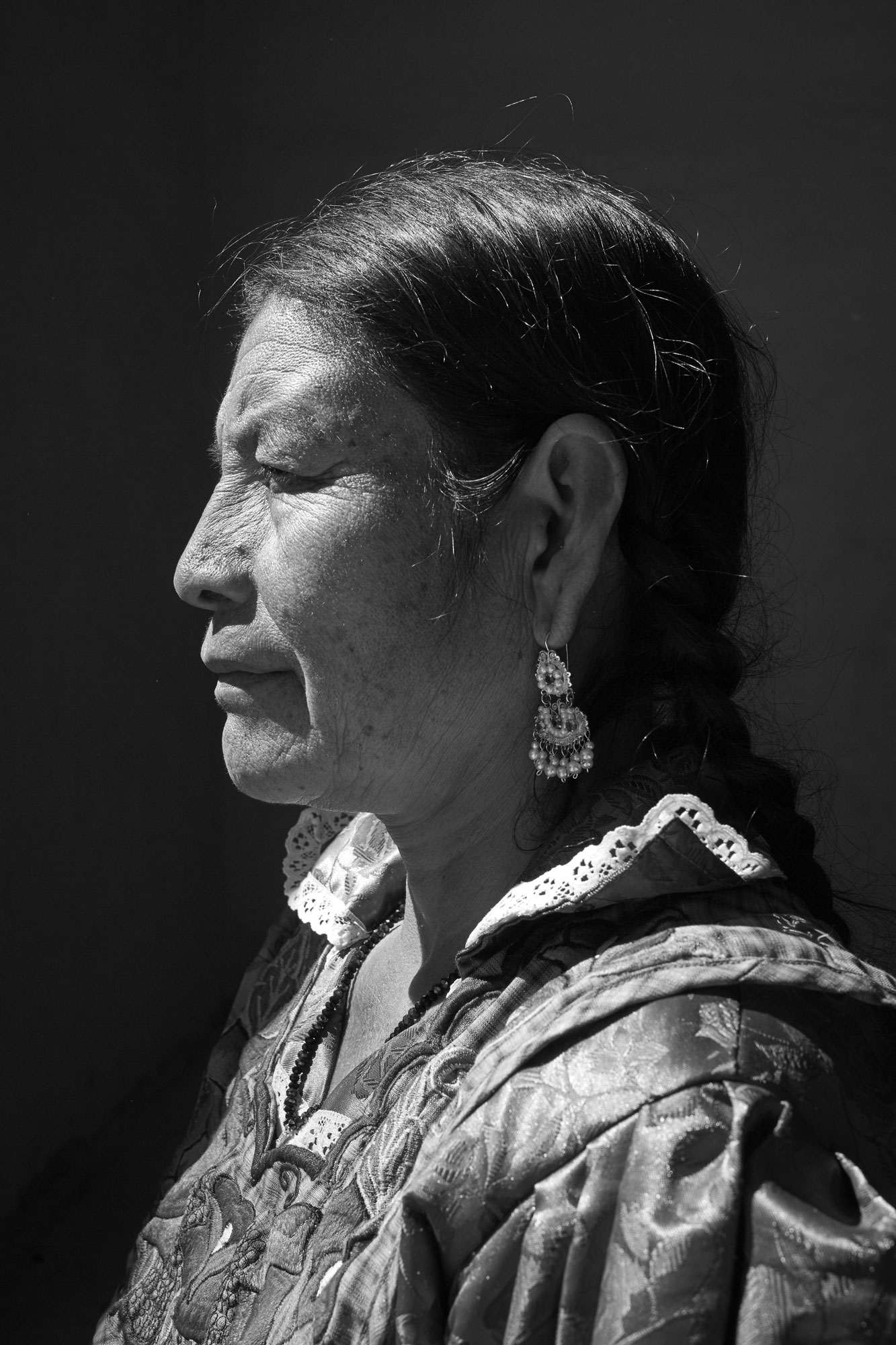

“In my life, mezcal is the only way to define the world. It’s part of my identity and I consider it my biggest passion, the greatest I will ever have. My experience in academia made me look back to the countryside and find in it the magueyes [agaves] that I had seen since I was a girl, the smell of cooked maguey that I am so used to smelling, and made it so that [what] once was commonplace to me became extraordinary; it has allowed me to see and think about mezcal from a different point of view. In my town I am one of the few women in my generation that was able to study and because of that I have the responsibility to open the gate for those who come after me. The goddess Mayahuel is associated with the feminine part of the plant [the leaf] as a giver of life. Mayahuel feeds the world, and is represented as the woman of 400 breasts: (as if each agave leaf was a breast and each one of her breasts would feed one of her 400 children). Because of the capacity the agave plant has to give us food…Mayahuel became a deity. There are very few feminine deities, and when there is one it’s related to the subject of fertility, reproduction, the capacity to give life.”

GRACIELA ANGELES CARREÑO is the general manager of Mezcal de Los Angeles (Real Minero), and is responsible for the production and commercialization of their mezcal for international export. She is the mother of two beautiful children.

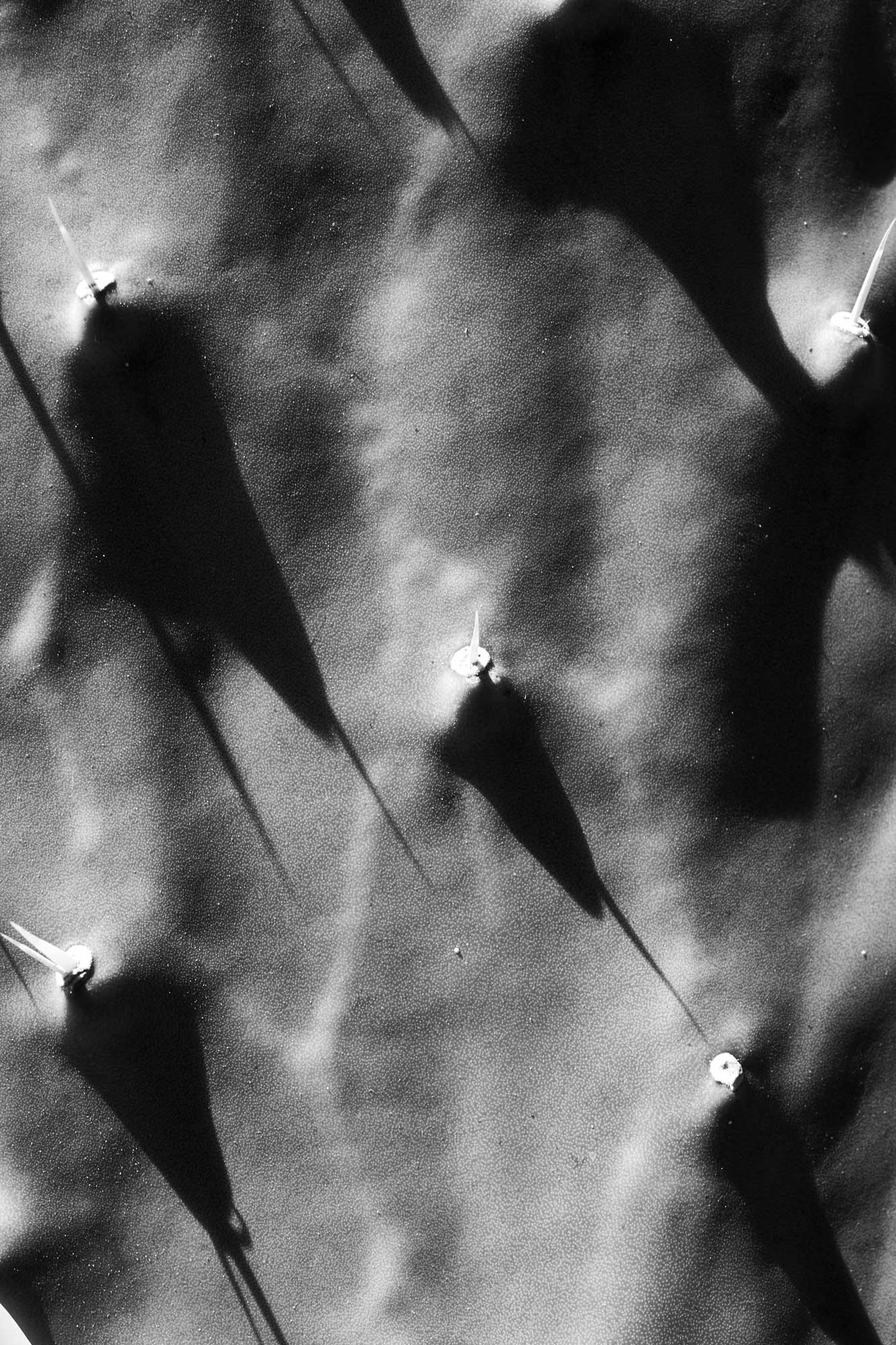

Andrea Gentl came to Oaxaca in January 2017 to lead a photography workshop with Pocoapoco, a Oaxaca based residency project that supports cross-cultural exchange of research, conversation,and community across creative fields. The photography workshop honed in on the region’s themes of craft, food, and mezcal—and the people and makers behind them. Most often these were women: in their homes, running their businesses, caring for their families, working at their looms, in their kitchens, identifying their passions. Andrea’s photographs effortlessly enter into the spaces and lives of the women who opened themselves up to her during this trip. Her portraits bring forth deep feelings of pain and joy, and capture the details and complexities of what it means to be a woman in Oaxaca. Feelings that, even for those of us present, couldn’t be captured until they were illuminated in her photos. As Andrea and I talked, our conversations kept circling back to our need for a deeper understanding of the nuance and complexity in the women we were meeting. Although the portraits captured an essence of these women, and though our brief interactions were kind and meaningful, we were missing the greater story of why we felt such a connection to these women and their daily lives. The portraits represented a narrative, and a culture, but what was the real story? How was this way of being so different from our own, and yet so directly related to our lives and experiences? While Andrea was visiting we came across a book of poetry called The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers, an abstract collection of works by Bahnu Kapil, based on a list of questions asked to women she met in her travels. Using Kapil’s book as inspiration, we considered these questions:

Where do you come from and how did you arrive here?

What do you believe in?

Who is your mother?

What have you overcome?

What do you see as your greatest achievement?

What are you pursuing?

How has your gender impacted your life, for better or for worse?

Who has empowered you?

Who do you empower?

Describe a woman who has touched or marked your life?

With these questions, what began as a series of portraits turned into extended conversations, performances, and meals with over 20 Oaxacan women, along with 12 other women from the US and Mexico. During one very hot week in April, we saw homes and trades, tasted food, heard stories, and learned about one another across cultures, generations, and countries.

Common threads quickly appeared between these women’s lives and stories, and our own: a belief in the powers of the universe, a drive to understand our purpose; a time in which we threw ourselves into the unknown and hoped we would land on our feet, a time in which we did—remarkably—land on our feet. Appreciation. Love. A desire to create community, a fierce need to prove independence. A time when we identified as changed, as modern, as new. Together we shared questions: how to give but not give everything away, how to fit in and also fight against, how to exist with drive, emotion, fear—how to turn that into something we believe in. In the five days we were together, nearly all of us cried. I think most of us shared more than we thought we would. We spent breakfasts, dinners, and car rides spiraling our way through widely varying histories of love, work, family, sex, children, bodies, feelings, and fears. I think, in many ways, we were each looking for a way to heal. We didn’t come to any direct conclusion, but there was something about our communication and consideration that made us feel less alone in our pursuits. Less adrift, and less daunted by each individual experience and challenge. We began to piece together a communal sense of strength, hardship, excitement, love, and raw emotion that brought our perception of womanhood into new light. Following are some of the words that we heard from Las Mujeres Fuertes, The Strong Women of Oaxaca.

“The goddess Mayahuel is associated with the feminine part of the plant (the leaf) as a giver of life.”

“In my life, mezcal is the only way to define the world. It’s part of my identity and I consider it my biggest passion, the greatest I will ever have. My experience in academia made me look back to the countryside and find in it the magueyes [agaves] that I had seen since I was a girl, the smell of cooked maguey that I am so used to smelling, and made it so that [what] once was commonplace to me became extraordinary; it has allowed me to see and think about mezcal from a different point of view. In my town I am one of the few women in my generation that was able to study and because of that I have the responsibility to open the gate for those who come after me. The goddess Mayahuel is associated with the feminine part of the plant [the leaf] as a giver of life. Mayahuel feeds the world, and is represented as the woman of 400 breasts: (as if each agave leaf was a breast and each one of her breasts would feed one of her 400 children). Because of the capacity the agave plant has to give us food…Mayahuel became a deity. There are very few feminine deities, and when there is one it’s related to the subject of fertility, reproduction, the capacity to give life.”

GRACIELA ANGELES CARREÑO is the general manager of Mezcal de Los Angeles (Real Minero), and is responsible for the production and commercialization of their mezcal for international export. She is the mother of two beautiful children.

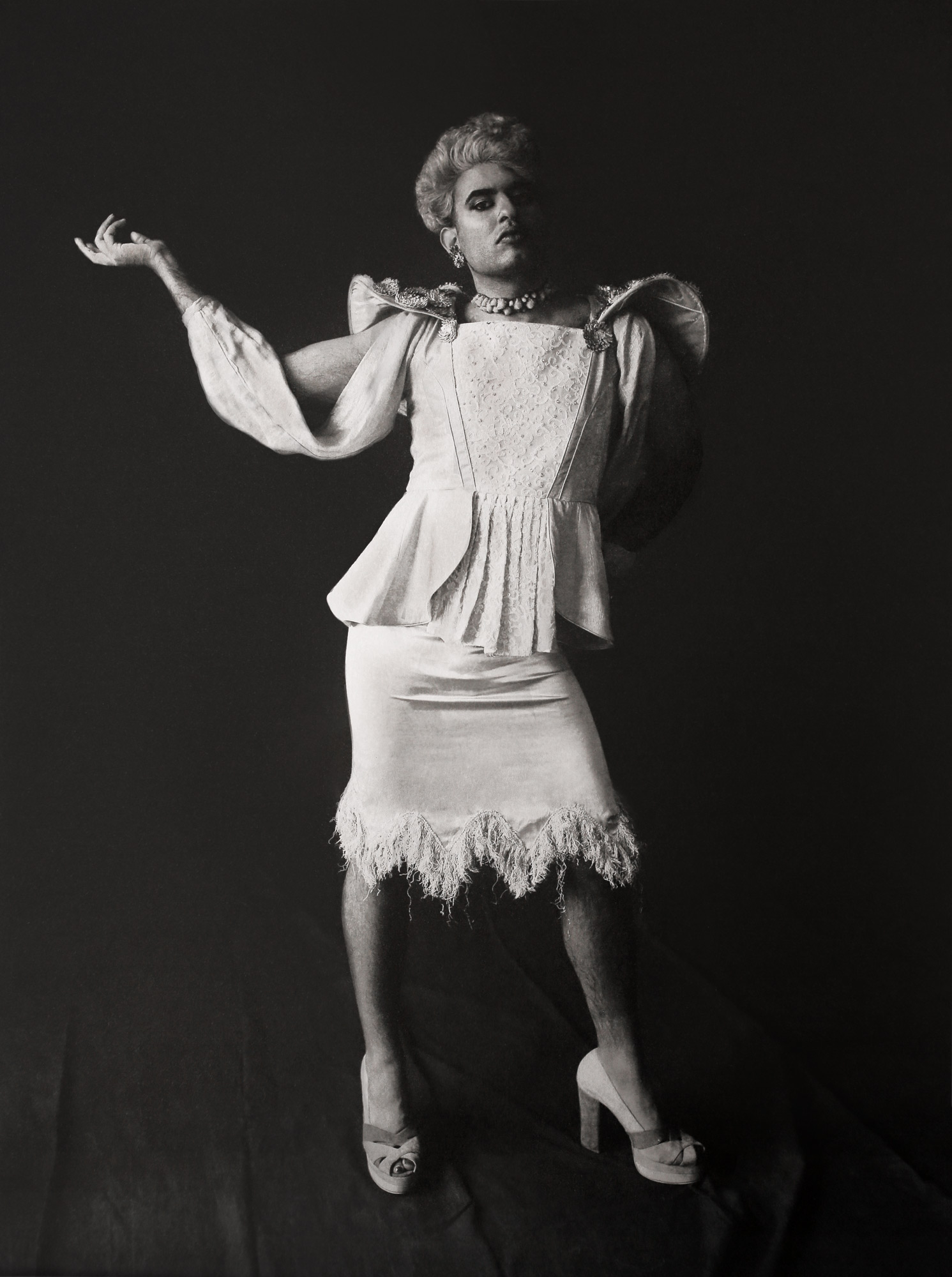

“In some Oaxacan communities, dances traditionally done by the men have begun to disappear due to migration to the United States. We are following the example of other women who have rescued the dances of their ancestors by taking on the male role, not only representing them but by appropriating the role that the dance suggested. In our company, we actively reaffirm that the roles of tango are not exclusively between man and woman, but that this dance/conversation can also happen between two women or, similarly, two men. Carla (my partner) and I are two very different women…yet through dancing the tango together we can talk, dance, enjoy, and share the movement of our souls.”

EVELYN MENDEZ is a Oaxacan contemporary dancer. She has been dancing since 2008, beginning in the Compañía Estatal de Danza Contemporánea de Oaxaca. In 2013 she left the company to work independently and in partnership with various artists. She has been collaborating with the Argentine tango dancer Carla Pais for four years.

“Carla (my partner) and I are two very different women…yet through dancing the tango together we can talk, dance, enjoy, and share the movement of our souls.”

“The most empowering thing about being a woman for me has been the opportunity to be part of a movement and find this community of strong women.”

PAULINA GARCIA is the founder of Suculenta, a food preservation and processing kitchen which focuses on local ingredients, sustainable practices, and food education. Garcia is also the sole female partner in Boulenc, a bakery working with traditional artisan baking methods as a way to transmit knowledge, exchange social and economic services, support a sustainable community, and create conscious consumption. Born in Coahuila in northern Mexico, Paulina has lived in Oaxaca for three years.

“I’m seeing a trend of women who are coming and returning to Oaxaca to make change. I like women in business. We are sensitive, we are generous, we are in it for the right reasons.”

SALIME HARP CRUCES is the co-founder of Xaquixe Glass Studio, an innovative and sustainable glass studio in Oaxaca. She is co-founder of Procesos Proambientales, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to help other artisans—in Oaxaca and Mexico—upgrade their production processes and adopt uses of renewable energies. She has lived in Oaxaca nearly all her life.

“I was born in the region of the Istmeño and grew up between Zoques and Zapotecas, and because of this my view as a woman is if I clearly know what I want I will get it. I learned to look at life as happy, naughty, and fun. To scare away any fear of my path and to look ahead. I say that the women of the Isthmus like to shine and accompany us, and that being a woman has no limit.”

DOŇA AURORA TOLEDO is the founder of Zandunga restaurant in Oaxaca City, a modern space serving traditional cuisine from the Isthmus region of Oaxaca. She promotes reading, loves the kitchen, and cooks for taste and passion. She is the mother of Marcos and Germán, the grandmother of Santiago, and the wife of Marín.

“My aunt, my Dad´s sister, is a nun and a missionary. She has taught me with her example that no matter what religion, race, culture, gender we are, we are all capable of having meaningful lives and making others’ lives meaningful as well, by being compassionate, kind-hearted, good-natured, empathetic, tolerant, and inclusive. She has been respectful and given me all the support to be the woman I am, although I am not religious and although I´ve chosen a different life among all my relatives. She has encouraged me to pursue my mission in life even if this means not to please others, but to be authentic.”

ANA PAULA FUENTES is the Founding Director of the Textile Museum of Oaxaca. She has worked in Barcelona, Mexico City, New York, and Oaxaca, designing textiles, collaborating with artists, and developing social platforms for artisans. Currently she is the Executive Director of CADA Foundation, a nonprofit organization that pursues sustainable local commerce through the empowerment of design and craft. She is also the Outreach Director of Traditions Mexico, which offers unique cultural tours focusing on master skills of artisans and their rich, backcactus world in the little-known, culturally diverse lands of Oaxaca and Chiapas. Originally from Mexico City, Ana Paula has lived in Oaxaca for ten years.

ABIGAIL MENDOZA RUIZ is the chef and owner of Tlamanalli, a Zapotec restaurant in Teotitlán de Valle which has been open for 27 years, which she runs with her 6 sisters. She has been in the kitchen since she was a small child, quickly gaining culinary knowledge as well as acknowledgement from her community and international followers. She travels often, teaching and feeding the others traditional Zapotec food, processes, and recipes.

PASTORA GUITEREZ REYES is a Zapotec woman: a natural dyer and weaver, a traditional healer and cook, and a community organizer. Alongside her mother, grandmother, and other women in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca community, she helped create Vida Nueva Weaving cooperative in 1997, the first all women’s cooperative in their village. Just 20 years ago, social rules limited gatherings of married women in Teotitlán to 30 minutes. During Vida Nueva’s initial gatherings, many husbands waited outside, knocking loudly when the time was up. Soon, most women with husbands left the group. Only the widows, single women, and women whose husbands had left for the states remained. Now, despite sexism, racism, and enormous cultural hurdles, Vida Nueva is 20 members strong, has slowly gained respect and acceptance in their village, and is now officially recognized by the village government. Not only do they sell their rugs as a cooperative—providing much needed financial independence—but Vida Nueva also offers community education in rarely addressed issues such as prenatal health, domestic violence, substance abuse, and gender inequality.

“I like women in business. We are sensitive, we are generous, we are in it for the right reasons.”